- ホーム/home

- About us

- 研究・各国動向/Research/Measurement

- スマートメーター/ Smartmeter

- 携帯電話基地局反対運動

- 5G & BRAG Project

- 過敏症対策/advice for EHS/MCS

- 書籍の紹介/books

- 学校環境/school environment

- Children's health and school

- A letter of request on School environment

- 各政党への公開質問状/open letter to political parties

- Global 5G Protest Day

- 関連記事/Articles

- LEN サポートチーム/LEN Support Team

- 病院紹介/Hospital

- リンク/link

- 問合せ/Contact us

Sapporo City Board of Education specifies consideration for electromagnetic hypersensitivity

In March 2021, the Sapporo City Board of Education released the Guidelines for the school Wi-Fi. It compiled examples of classes using information and communication devices and cautions.

"Measures for electromagnetic hypersensitivity" was also mentioned.

While explaining that electromagnetic hypersensitivity is not an official diagnosis and that the scientific basis is unclear, the guideline admitted that "it is true that there are people who complain that they suffer from disorders.".

When children or their parents or guardians consult to school, teachers have to provide concrete measures to reduce electromagnetic waves, such as turning off electronic devices after use and unplugging electrical outlets.

The Sapporo City Board of Education has tried to keep track of the number of students with sick house syndrome, multiple chemical sensitivity, and electromagnetic sensitivity, and has called for measures such as turning off wireless LAN (Wi-Fi) signals when children with electromagnetic sensitivity or their parents complain.

But in reality, it was largely up to the teachers to turn it off, and some schools refused to turn it off. In the guidelines, it specified measures for children with electromagnetic hypersensitivity, which will help to protect the health of children.

Sapporo Board of Education Guidelines showed as below, in page 36;

Measures for electromagnetic hypersensitivity

Electromagnetic hypersensitivity is not an official diagnostic term, and the government and the World Health Organization (WHO) have stated that there is no scientific basis for linking the symptoms to exposure to electromagnetic fields. However, it is true that there are people who complain that various physical disorders occur due to exposure to electromagnetic fields.

If children or their parents or guardians consult us about electromagnetic hypersensitivity, we will take measures such as turning off the power switch or unplugging the electrical devices after use. For electronic devices that do not have a power switch, a power strip with a switch can be used to turn the power on and off smoothly.

by Yasuko Kato

Consideration for child with electromagnetic hypersensitivity

Yuta, who lives in Shizuoka Prefecture, started EHS at the age of eight and later developed MCS.

The public junior high school that Yuta was going to enter had a wireless LAN, but in March,2017, just before he entered the school, they switched to a wired LAN for him.

Because Yuta also reacts to electromagnetic waves from fluorescent lights, teachers turned off them during class. Yuta took refuge, and took classes in a separate room, when it was dark and fluorescent lights were needed, when other students used computers, electric tools, electronic blackboards, personal computers or chemicals, and when he reacted to synthetic detergents and the fragrance of softeners.

Though students with hypersensitivity often have to study on their own under the pretext of "separate room classes," teachers at this school have always accompanied to Yuta. So, he was able to study almost like a regular class.

by Yasuko Kato

Children with EHS/MCS and environmental issues in Japanese schools

Written by Yasuko Kato/ Journalist, Director, Life-Environmental Network/ July 7, 2019

Translation assistance by Pat Ormsby

EHS and MCS in Japan

In Japan, the sick building syndrome or sick house syndrome (SHS) was recognized as a disease-causing factor according to the ICD-10 code T529 ”toxic effect of unspecified organic solvent” in 2004, and MCS was also recognized as a disease according to T659 “toxic effect of unspecified substance” in 2009. However, there is not enough social recognition of MCS. Most people in Japan including medical care professionals do not know little about MCS.

Electromagnetic hypersensitivity (EHS) is still unknown to the general population. The estimated prevalence rates of MCS is 7.5%, and that of EHS is 6% in Japan.

I carried out a questionnaire surveywith Dr. Olle Johansson, Sweden, that found 80% of EHS participants also developed MCS. Our report noted that half of the EHS participants could not receive medical treatment due to lack of information about it among specialists and hospitals.

Children and the school environment

I conducted an interview with 10 children who had EHS, MCS or SHS and their parents in 2017. They faced unsympathetic attitudes and ignorance about their symptoms. In 70% of these cases both the mother and child were hypersensitive.

One boy (8years old) with MCS and EHS was called “crazy” by his grandfather. This boy couldn’t enter his classroom due to the perfumes in softeners or detergents that volatilizing from his classmates’ clothing. He had to study by himself in another classroom without a teacher. His mother asked to the board of education and principal to establish a special care classroom for children with poor health. If it were established, he could learn from a teacher. The board, however, did not accept her request. She lobbied every way she could, including approaching assembly members and the mass media. After two years of efforts she could finally get a special care classroom arranged.

One junior high school girl (15years old) with MCS and EHS was transferred from a different school four months before graduation. She suffered effects from microwave radiation from Wi-Fi and also effects from pesticides, floor wax and chemicals used in repair works in the school. She had always loved sports before she got MCS and EHS, so she joined the volleyball club as a manager. Even if she could not play volleyball, she wanted to get be involved in sports. The teacher who directed the club, however, forced her out. The teacher said “I can’t be responsible for what might happen to her”. She and her parents asked the school to reconsider its decision, but it wouldn’t.

Some schools help children with MCS/EHS stay involved. One elementary school nurse made a poster appealing for fragrance-free consideration. One junior high school removed Wi-Fi, and installed a wired network for a new student with EHS. But, such humanitarian schools are rare. I have written about those instances in my book” Sick school issues and measurement” (in Japanese).

A questionnaire survey of children

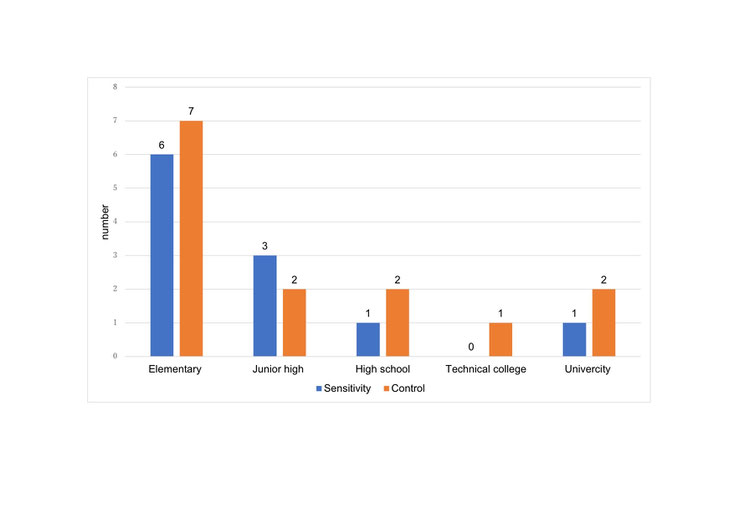

After that, I conducted a questionnaire survey of children and students with EHS, MCS or SHS, with healthy children as a control group. I got 11 replies from the sensitive group and 14 replies from the healthy (Graph 1). The average age was 11years in sensitive group, and 13 years in the control group.

Graph 1. Questionnaire participants

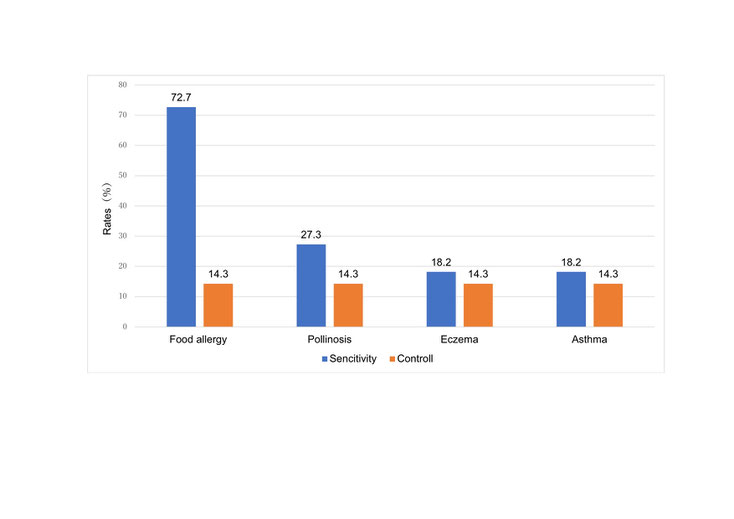

Most of the sensitive group had also developed food allergies (72.7%), but among the control group only 14.3% had (Graph 2, P<0.05). There were no significant differences, however, in pollinosis, eczema or asthma.

Graph 2. Participants allergy rates

Using two questionnaires, I examined what symptoms were occurring at school. One was the Quick Environmental Exposure and Sensitivity Inventory (QEESI) for screening MCS that was developed by Dr. Claudia Miller, and the another one was an EHS questionnaire developed for screening EHS by Dr. Stacy Elititi. Both questionnaires were adjusted for Japan by Dr. Sachiko Hojo. The medium scores of the sensitive group were significantly higher than those of control group (p<0.001).

|

|

Sensitive (n=11) |

Control (n=14) |

Cut-off value* |

|

QEESI score Q1 chemical intolerance Q3 symptoms Q5 disturbance of daily life |

61 28 43 |

19 4 3 |

40 20 10 |

|

EHS score |

53 |

26 |

47 |

*The cut-off value was estimated for Japanese adults. There is no cut-off value for children in Japan.

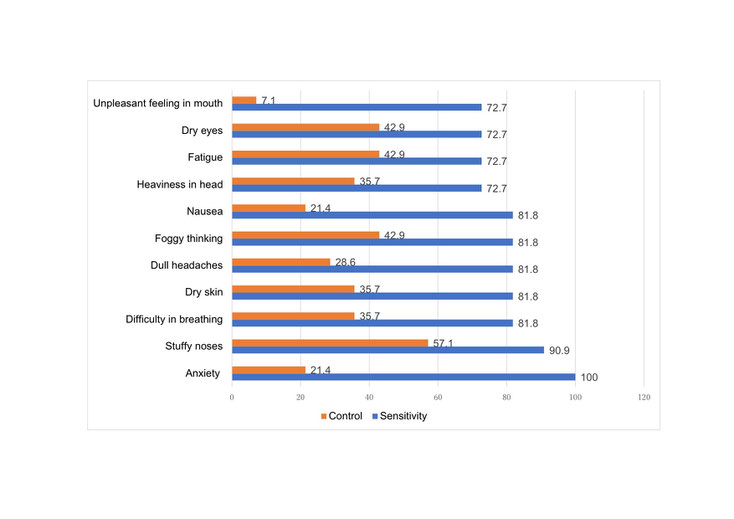

Graph 3 shows major reported symptoms. More than 80% of the sensitive group suffered from anxiety, stuffy noses, difficulty in breathing, dry skin, dull headaches, brain fog, and nausea. Healthy children also shown to experience health problems at their school.

Graph 3. Reported major symptoms in school

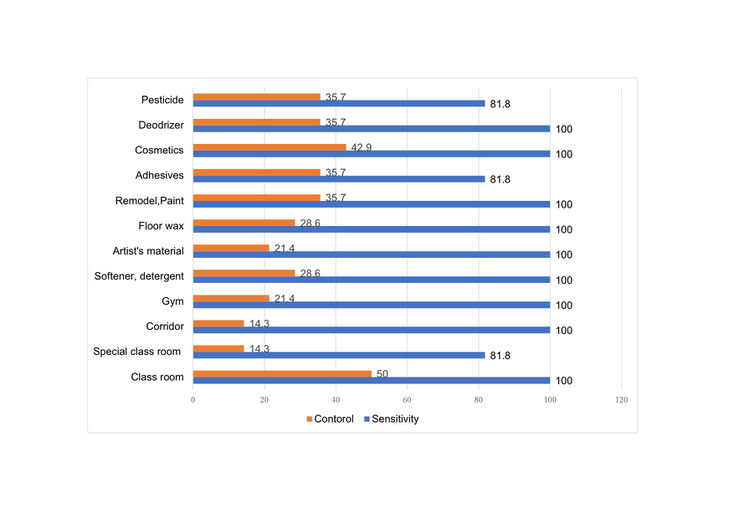

I asked “What do you think causes your symptoms?” and “Where do you get sick?” (Graph4).

Graph 4. Reported causes and places

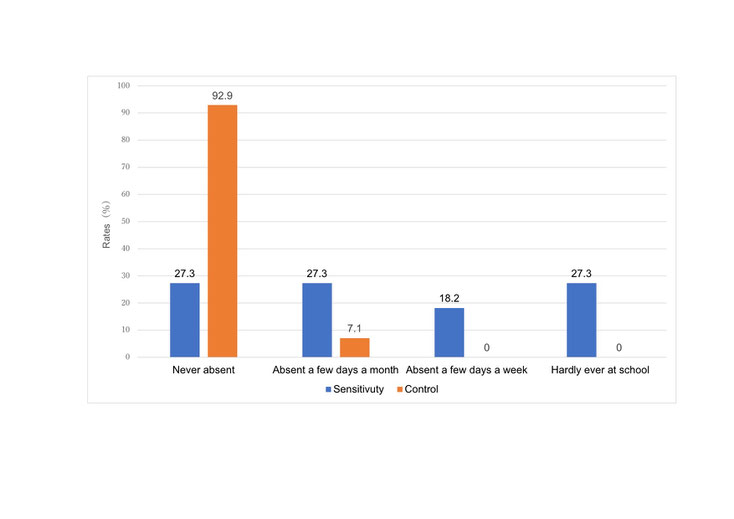

I also asked about attendance. In the sensitive group, only 27.3% were “never absent”, 27.3% were“absent a few days a month”, 18.2% were “absent a few days a week”, and 27.3% were “hardly ever at school”. Thus, 72.7% of the sensitive group had difficulty going to school (Graph 5).

Graph.5 Attendance

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) issued a guideline “Maintaining a Healthy Learning Environment”to help children with MCS and SHS in 2012. It recommended use of wax low in volatile organic compounds and avoidance of air fresheners and deodorizers. It recommended ventilating the classroom to reduce the concentrations of chemical substances, if the child's symptoms were mild, and to practice home-visit lessons, if the child's symptoms were severe enough to make attending school difficult.

Many local governments developed the guidelines to reduce health problem in schools. For example, Asahikawa City, Hokkaido, recommends conducting a health survey of children before and after relocation (for three months) to a school building that has been newly built or rebuilt. If symptoms or signs of illness are seen, the person in charge must immediately report them to the city. Parents and teachers are asked to reduce their use of perfume, cosmetics and hair cream. The guidelines also mention health problems related to EMFs (mobile phones, TVs, microwave ovens, personal computers and high voltage lines), and recommended inquiring into the environment in children’s homes. Moreover, it advised antioxidants supplementation, diet therapy, sweating to stimulate metabolism, and getting good sleep if the children experienced any health problems.

Text book ink measurements

Many children experience health problems due to VOCs from text book ink. Some parents asked MEXT to reduce the VOCs from text books in 2000. MEXT examined text book VOC levels from 2003 to 2005, and published measurementsof four versions of textbooks:

1) Sun-dried version: dried in the sun at the school or at the home,

2) Cover copy version: Most of the VOCs volatilize from the cover of the text book, so a copy is made of the text book cover, and wrapped over the cover.

3) Full copied version: all pages copied,

4) Photo-catalyzed paper cover version: photo-catalyzed chemical paper used for the text book cover.

Parents can tell the school in advance which version they want. The most used version is sun dried.

Wi-Fi in school

Wi-Fi in school has been rapidly spreading in Japan since 2014. The government and the board of education recognize chemical risks, but they do not consider EMF risks. In Japan, the media rarely report on health problems as being related to EMFs. As the Japanese government has not adopted the precautionary principle when making policy decisions, the EMF health problem is underestimated.

Wi-Fi in schools, however, is apt to become a huge problem soon. More research is needed to elucidate related health problems in schools to protect the health of children, teachers and staff.

サイト内の文章、イラスト、写真の無断転載および営利目的の使用を禁止します。違反した場合は法的な措置をとります。